How much can you know about a man just by looking at him?

You can see his tattoos, his surgically repaired knee, the cuts on his legs, his empty ear piercings, the cigarette burns on his arm, and the lines on his face, but you can’t see their causes. Nor can you see his past, his demons, his politics, his religion, or his sexual orientation.

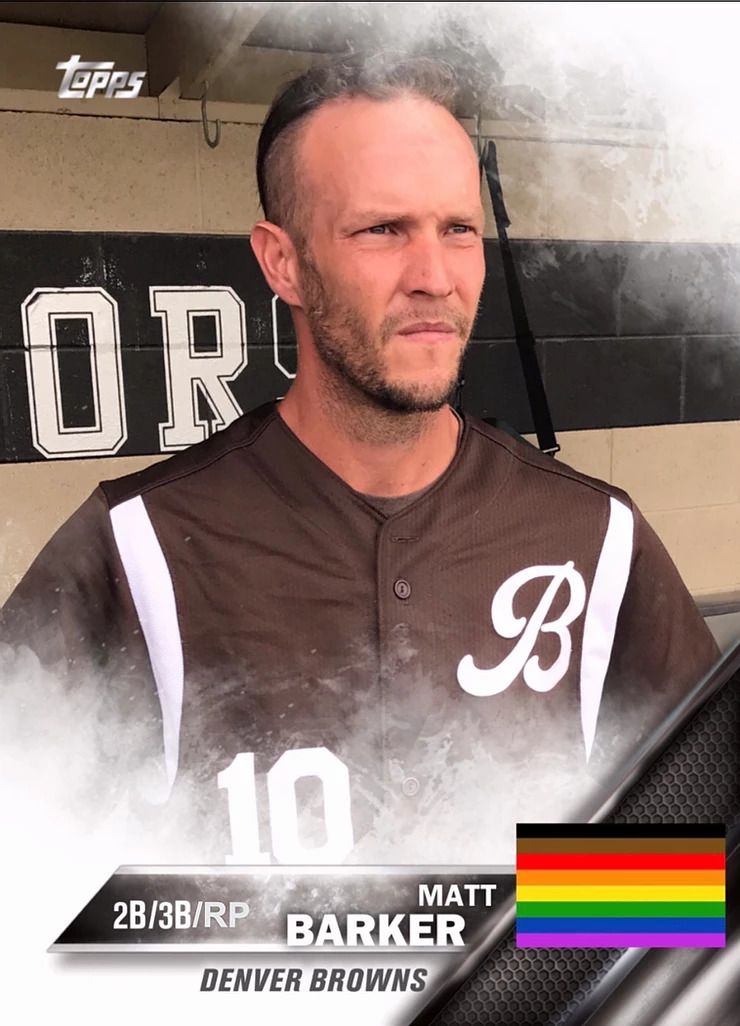

Upon meeting Matt Barker, you would immediately be able to tell that he spends a lot of time in the sun, and from his frame you might be able to surmise that he’s an athlete. But you would never know that he was once the best player on a state championship-winning baseball team. Or that he was drafted by the Colorado Rockies. Or that he squandered his twenties with alcohol, painkillers and self-loathing brought on by having to hide his homosexuality.

Barker is 35. He lives in Longmont with his brother and he works at a cemetery. On Sundays he plays second base for the Denver Browns of the National Adult Baseball League. If you had asked 17 year-old Matt Barker where he saw himself at 35, it probably wouldn’t have been here. But that Matt Barker also didn’t know just how difficult the next fifteen years of his life would be, or that the Matt Barker I interviewed in 2017 would be the happiest he’d ever been.

I can’t tell you what kind of home Barker keeps, because I interviewed him at his sister’s house. She lives a few blocks away and he’s taking care of the place while she’s out of town. We sat down on the back porch on a beautiful, hot Saturday afternoon, joined by his sister’s old dogs Tucker, who is blind, and Lucy, who is going deaf, and he started to tell me about his life.

He was a baseball prodigy practically from the time he would walk. His parents told him stories of him hitting a wiffle balls over the fence of their yard at age two. Growing up as a kid in Southern California, his only competition was himself. “When I was younger, I didn’t really play with anybody who was as good as me, so I had to set a goal for myself to try to surpass.” He knew he was a special player, but he also knew something else about himself that wasn’t obvious to everyone else.

One day when Barker was ten years old he was watching the Atlanta Braves at home on TBS, and he saw David Justice on his TV screen. “I thought he was the hottest thing in the world,” Barker remembers. He told his mother and sister, and their reaction convinced him that this was something that he had to keep to himself, no matter what it took. “I started to cry. And based on the way they reacted I thought, ‘Well, I better not bring any of this up again ever.’ I pretty much just locked it down from there. And that’s the most unhealthy thing ever.”

Lucy starts licking his legs, and I notice that they’re covered in red marks. “I made the poor decision to wear shorts while weed whippin’ at work,” he explains with a slight twang that isn’t easily traceable to SoCal or Longmont, but that sounds just like a ballplayer giving a postgame interview. Barker can be funny and amiable, but there’s an underlying seriousness to him. You can tell that he means what he says and that he doesn’t enjoy being messed with.

As a kid, he was hypersensitive, and it wasn’t uncommon for him to get into trouble. “I used to get into fights all the time in California. I remember throwing a chair at a kid once.” Things improved somewhat when his family moved to Longmont when he was 11 years old, but his proclivity for overreacting would continue to dog him into adulthood.

“I don’t like the way people talk to me sometimes. You know, when they talk down to me. Even when I was little it bothered me. If they’re talking down to you that means they think they’re above you and that’s just not true.”

By the time he got to Niwot High School, no one was above him on the baseball field, but he still felt like an outsider. He tried dating girls, and he took one to prom, but it didn’t feel right. Everyone knew his name, but he didn’t get invited to parties.

“It was difficult to try so hard to fit in and still feel like you weren’t part of the crowd or the group, but it always felt that way.”

No one ever accused him of being gay to his face, but he was constantly worried that there were rumors floating around the school, even though he’d never had a gay experience. By his junior year his thoughts were turning to playing professionally, and there seemed to be no reason why he couldn’t do it. Barker hit over .500 as a junior, in addition to going 9-0 as a pitcher. He hit four home runs in a game. On the mound, he threw a perfect game. The Boulder Daily Camera and the Longmont Times Call named him county player of the year, and his coach said he was the best hitter he’d ever had at Niwot. The Cougars won their second consecutive 4A State Championship, and scouts had him going anywhere from the third to tenth rounds in the 2000 MLB Draft.

Then, like so many other promising talents who don’t make it to the big time, came the injury. In Barker’s case, it was a torn labrum in his throwing shoulder; suffered the summer after junior year. Doctors recommended he take time off to rehab it fully, but it was his senior season and he wanted to help his team. As a senior he hit even better than he had the previous season - an astonishing .627 with a slugging percentage of 1.478 - but he didn’t pitch at all because of the injury. Niwot won their third consecutive 4A championship, but his draft stock fell. He was eventually selected in the 46th round by the Colorado Rockies, who wanted him to go to college to build his arm strength back up, with the possibility that they might select him higher the following year and put him into their farm system.

Barker didn’t want to go to college, but it seemed like his only option. In the fall of 2000, he headed to Midland, Texas to play for Midland College. It was the beginning of a dark period of his life. ★ ★ ★

Just as he had feared, college wasn’t for him. “I just didn’t handle it well. I made the wrong choices.” He didn’t get along with the coaches. He thought they had too many rules (like not being allowed to wear high socks). He drank too much. By early November, he had withdrawn from Midland and was back in Colorado. In early 2001, he had an emergency appendectomy that landed him in the hospital for six days. Two weeks later he had a private tryout with the Rockies. It didn’t go well. Colorado did not select him in the 2001 draft. He didn’t give up. In the fall of 2001 he enrolled at Lamar Community College in Colorado. If that seems like a long way from the majors, it’s worth noting that one of his teammates was Brandon McCarthy.

Barker fit in better at Lamar than he had at Midland, but the problems were still there. “I was drinking way too much and not going to class and then I’d make stupid decisions like this.” He shows me the faded cigarette burns on his left arm that he got with a teammate as a sign that they were going to be ‘boys forever’. “I haven’t seen him since then.” At that point, I had to ask him about the colorful Egyptian themed tattoos on his right arm. Turns out those are far from drunken mistakes. Barker has had an interest in ancient Egypt since learning about it in the sixth grade, and he’s gotten the tattoos over a period of several years. Unlike his interest in Egypt, Barker spent most of his life keeping his sexuality as far from the surface as possible. “I hid it well. I didn’t let myself think about it at all.” But no one can fool everyone all the time, and one day at Lamar he let something slip. “I said something about Denzel Washington. I think Training Day had just come out and they all looked at each other and looked back at me and I was just like, ‘Yep.’” Eventually, Barker’s temper got the best of him, and an argument with the head coach at Lamar resulted in him being kicked off the team. “One specific incident happened. I said the wrong thing. He said the wrong thing. And that was that.”

“If you’re always out there partying and everybody knows this, it’s easy for someone to point the finger, even if you don’t do anything wrong.” Despite two bad experiences, he decided to try college one more time. In the spring of 2002 he headed to Otero Junior College in La Junta, Colorado. By that time, his off the field issues were spiraling out of control, and playing baseball was no longer fun. Barker lasted longer at Otero than his previous two colleges, but he left after being blamed for an incident at a party in November 2002. Barker wasn’t responsible for what happened, but he concedes that “if you’re always out there partying and everybody knows this, it’s easy for someone to point the finger, even if you don’t do anything wrong.”

After he returned home; having dropped out of college for the third time in two years, Barker realized his dreams of playing professional baseball were over. “I came back from there and I said to my mom, ‘I’m done playing baseball,’ and she said, and I think she was trying to call my bluff, ‘Okay. Tomorrow you have to go work for your dad.’ My dad installed carpet. And I said, ‘Okay.'"

He didn’t pick up a baseball for three years. “I just drank every day. And installed carpet. That was all I did.” “I just drank every day. And installed carpet. That was all I did.” Barker spent the next several years trying to drink himself to death. He didn’t succeed, but he put on almost a hundred pounds and fell into deep depression. “My outer appearance really reflected my inner thoughts of myself. Essentially all of my 20s were lost to self-loathing.” He felt like a failure to his family for blowing his chance at becoming a professional baseball player. Then there was his knowledge that he was gay, and his unwillingness to come to terms with that. “I remember telling myself that I won’t ever be loved. I’m not gonna be the person that I wanna be. And all this other stuff. And that really makes it easy to drown all your sorrows. And it’s unfortunate because that’s pretty common.” Indeed, Barker’s experience when it comes to his sexuality is far from unique, but he’s one of the few baseball players at any level who has ever talked about it. ★ ★ ★

It’s getting pretty hot on the porch, and we’re out of soda, so we decide to move to the basement. Waiting there is his sister’s cat, Miss Delilah (Miss D for short), whom Barker rescued from an empty storage locker more than ten years ago. Lucy and Tucker follow us down the stairs and sit next to us on the couch as the conversation resumes. I asked him whether he ever felt uncomfortable in baseball’s sometimes homoerotic locker room culture, or if he ever felt attracted to another player on one of his teams. “I was so determined to make sure that I didn’t let on at all that I wouldn’t do any glimpses or anything like that. I was scared to death.” He pauses for a moment. “Having said that...”

In Barker’s senior season, Niwot trailed the state championship game by two runs going into their last at-bat. He was up first in the inning, and in his last high school plate appearance he hit a home run that observers claimed landed on the highway beyond All-City Field in Denver. Niwot continued the rally, and the score was tied with the winning run on third when coach Bob Bote called for a squeeze bunt and time stopped for Matt Barker. “Our ace pitcher and I were standing arm and arm and it was our last at-bat of high school. We both knew we were getting drafted. And we saw the coach call a play and we just looked at each other and locked eyes and I swear if I was going to kiss anybody I might have kissed him right then. And he’s straight and I think he’s got a family now. But it was one of those moments where you’re so happy and you could feel the moment turning and the crowd roaring behind you. And then I just looked back out at the field. The play happened and the guy scored. We won. Dogpile. That was probably the closest to letting it out.” “We just looked at each other and locked eyes and I swear if I was going to kiss anybody I might have kissed him right then.” In the spring of 2005, just five years but a lifetime after that moment, Barker got a call from an old teammate who asked if he wanted to play baseball again. He realized that he did, and he joined the Colorado Reds of the National Adult Baseball League. In a sense, the ending of his self-imposed exile from the game he loves can be seen as the beginning of his climb back, but it isn’t that simple. He was still drinking every single day, and it hurt his performance on the field. He couldn’t see the ball the way he used to, and he weighed 260 pounds. Finally, in 2007 he made the decision to stop drinking after having been an alcoholic since he was in college. This was a positive step for Barker, but he still wasn’t happy. “I was doing all the wrong things, and I was beating myself up because I wasn’t out. It wasn’t like all the off-the-field issues were caused by holding all of this in. I was still making poor choices. But it definitely had a big role in it.” His coping mechanism switched from alcohol to painkillers, which he was dependent on for the next six years. “I was never awake without it. And that’s a vicious cycle.” Barker’s life continued largely the same as it had before he quit drinking. He installed carpet. He played baseball on Sundays for a number of different NABA teams, and he didn’t allow himself to get too close to anyone. After high school, Barker didn’t even try to date women. He knew exactly who he was, but he couldn’t face it. In late 2013, at the age of 31, he called up his sister and told her he was done being dependent on Oxycodone to get out of bed in the morning. On January 28, 2014 he flushed the last of his pills down the toilet, and he stayed at her house while he went through withdrawal. “The hardest part about that, other than the physical symptoms, is the mental tricks your brain will play on you.” Over time, he learned to ignore the aches and pains, real or imaginary, that his body would feel. “I’d rather have pain than go through all that again.” “I’d rather have pain than go through all that again.” After not playing in the NABA in 2013, Barker decided he wanted to play baseball again. He contacted his old teammate, who was playing for the Denver Browns, and joined the team. Now sober for the first time in almost fifteen years, he found himself having fun again. Then, just as he was finally starting to enjoy himself again, he tore his ACL trying to avoid a collision at first base. The injury required surgery and rehab. Barker did it all without any anesthesia or painkillers. The fear of becoming addicted again was too strong. Rather than fall back into his old habits, he used the rehab process as an excuse to get back in shape. He didn’t weigh as much as during his drinking days, but he was still around 220 pounds. So he started running and working out four times a week. Before he knew it he was back down to 165; the same as when he graduated high school. Looking at him now it’s almost impossible to believe he was ever overweight, but he says he’s got the “tiger stripes” on his stomach to prove it. Sober and healthy, Barker knew that there was one more thing he had to do before he could really start living again. He had to confront his sexuality. After giving it some thought, Barker finally accepted what he had known since he first saw David Justice on his TV at the age of ten. In September of 2015, he had his first sexual experience with a man. Two months later, he told his brother. It wasn’t until February that he worked up the courage to tell his parents and his sister. “For whatever reason I was more worried about telling my sister than anyone else. Maybe I thought she would be disappointed. Mom and dad were scary enough, but they’re good people. I didn’t think that they would just disown me or anything. My mom cried, but I imagine that’s pretty common.” And his sister? “She’s the most adjusted and understanding of any of us.” He found a boyfriend, and he publicly announced their relationship on Facebook. A lot of his friends were shocked. “People said that I hid it well and I was like, ‘Yeah, just imagine how hard that was. To be so scared all the time that I had to act that way.’” Some of his old baseball friends haven’t interacted with him as much since then. “I think I was most disappointed by my baseball coach from high school. He hasn’t said one word since then. We were pretty close, and I credit him for most of my success.” Whatever success Barker has on the field these days can be credited solely to himself. When he joined the Browns for the 2016 season, he wasn’t hiding anything anymore. The team knows he’s gay, and it hasn’t been an issue. “They don’t like move away in the dugout or anything. I don’t have to sit by myself. If it was like that I’d have something to say for sure.” His situation at work is different. He’s out to his boss, but not to his coworkers, many of whom still harbor homophobic beliefs and stereotypes. “One of the new guys said that the whole world was getting soft because of all the gays. And he’s literally saying this to me. And I’m like ‘Really? Really?’ It’s just the dumbest things that people say and I get a little kick listening to stupidity come out of people’s faces.” But he still doesn’t feel like he can bring up the subject of his own sexuality in an environment where “that’s so gay” is still a common expression. “Unfortunately two of the guys who are the worst about it have been to prison, and I’d rather not try to defend myself at a cemetery where there’s already holes dug.” Out in public, however, it’s a different story. Barker doesn’t intentionally try to hide his sexuality. In fact, he told me that he had arguments with his ex-boyfriend because he wanted to hold hands in public more than his boyfriend did. “I have people tell me, ‘Well you don’t really put it out there,’ and that’s because I never let myself live in that world, even in my own head. So to actually be in that world now…I want to go out and experience things.” And no, Matt Barker doesn’t “sound” gay, whatever that means. Nor does he “look” it either. Last year at Pride he wore earrings for the first time in years. He got his ears pierced at Otero in another team bonding escapade, but stopped wearing earrings after they kept getting snagged while installing carpet. He allows himself to wear bracelets and jewelry too, and he grew out his hair, which he had been shaving for years, “before it’s all gone”. He even styles it before he goes to work now. So far no one has said anything. ★ ★ ★

In August of 2016, Barker tore his meniscus. Surgery, again. Still no medication. Even after a second operation on his knee, he wanted to keep playing. “Baseball is the funnest thing in the world. There is nothing better than baseball. You’re constantly striving for perfection in a sport where it’s impossible to be perfect. It makes it analogous to life. Can you persevere through failure?” “There is nothing better than baseball. You’re constantly striving for perfection in a sport where it’s impossible to be perfect. It makes it analogous to life.” Barker certainly has persevered through failure in his life, but that’s not the only reason why he keeps coming back to baseball. He’s a ferocious competitor, and baseball is one of the things he’s really, really good at. When not on the field, Barker finds a way to work competition into almost every facet of his life. He and his sister share a brain in this regard, and they always try to have the last word when talking to each other on the phone. It kills him that his brother is better at darts. At the cemetery, he tries to whack weeds the fastest. And then there was the t-shirt design event he went to a few weeks ago. “At first I was like, ‘I’ve never done this, this is going to be difficult, just give me something easy.’ And they’re like, ‘Well it’s a competition, so try.’ And I said, ‘What’s your hardest stencil?’ I got second place.” These days he’s also trying to inspire his parents and brother to get in shape the way that he did, and he dreams about being able to do outreach in both the baseball and LGBT communities. “I think something that would be pretty cool would be to be a marketing ambassador for the Rockies in the LGBT community. And just bring more [LGBT] awareness to the sport of baseball.” Whether or not he gets to realize those ambitions, Barker is the happiest he’s ever been both on and off the field. “Before I stopped drinking, playing just wasn’t fun. But it’s been fun the last couple years. I’ve been happy and smiling. For the longest time I didn’t smile, but people tell me I have a nice smile so I’m trying to use it.” He’s also trying to make up for lost time. “I was thinking, ‘I need to experience everything that I missed as quickly as possible.’ I was so closed off for so long, and now I’m not. I wanna live. Because that’s the most important part. Living with who you are and being happy about it. There’s really no other way to live. It’s too depressing otherwise. I know this for a fact.” Last June he went to Denver Pride for the first time. This Friday he’ll be at Coors Field’s first Pride Night in over a decade. While Pride Nights have become more common across baseball in recent years, there still aren’t any out gay players at the major league level, and Barker understands better than most why it hasn’t happened yet. “My thinking was that I would rather make it first (before coming out), rather than have everything disappear because of that. If you have potentially millions of dollars on the line and you come out and that all goes away, even if you were better than all the others, you’re eliminating that chance.” If those fears sound unrealistic, just ask Michael Sam. Baseball is still waiting for its gay Jackie Robinson—a player talented enough and strong-willed enough to perform at a major-league level on the field despite the added scrutiny. Had things broken differently, Matt Barker could have been that person, and he has some advice for any MLB players who might be in a position to be The One. “If you aren’t comfortable standing out in front of it, then maybe you shouldn’t. But so much good is done when somebody is brave enough to do that. And that is, on a social scale, probably more important. Because staying hidden and all of that doesn’t really help anybody who would go through a similar experience.” Helping others is what Barker wants to do most now. Too many gay people in this country struggle to accept their sexuality, and too many teenagers and young adults of all sexual orientations squander opportunities because of drugs and alcohol. Barker has done both, and he hopes that his story can help prevent others from going down the same path. And he has choice words for pro athletes and potential role models like Daniel Murphy who make homophobic statements to the press. “What if a player looked up to him before that? And then they end up going the route that I went, which I wouldn’t wish on anybody. Or they just outright quit. The game of baseball is for everyone. If you can play, you should play. It’s the greatest game we’ve got. It’s one of those things where you can still feel like a kid even when something as much as millions of dollars or injuries and surgeries and all of that is on the line.” “The game of baseball is for everyone. If you can play, you should play. It’s the greatest game we’ve got.” ★ ★ ★

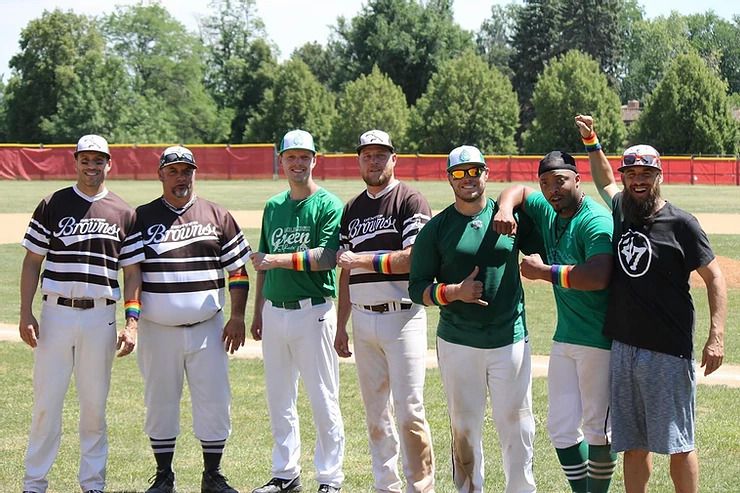

The day after the interview, Barker is out there on the field with his surgically repaired knee and a torn rotator cuff that he suffered several years ago but hasn’t yet had fixed. His Denver Browns are taking on the Denver Hops at a high school field in Aurora. Perhaps 25 people are in attendance; mostly friends and family of the players. Kids return foul balls in exchange for 1993 Fleer baseball cards from Browns owner Matthew Repplinger’s personal collection. Score updates from the Rockies game against the Cubs are relayed through the crowd and to the umpires. It’s a laid-back atmosphere in the stands, but the vibe is far from casual on the field. This is the highest level of the NABA, and they play nine inning games with wood bats. Almost all of these players had serious goals of playing professionally, and it shows. No, the level of play wouldn’t be confused with a minor league game, but you can tell these guys still take the game seriously. A fight nearly breaks out after a collision at home plate. Players slam their helmets down in frustration after striking out. Everyone gives maximum effort. Today Barker is in right field instead of his usual second base, but even there he makes an impact. Early in the game he nearly runs down a popup that he had no business being anywhere near. “Man, check out the range in right field,” is heard from the Hops dugout, followed by, “Nice effort, 10!” from another member of the opposing team. Even at 35, even after two knee surgeries, Barker is still faster than almost anyone on the field. And, despite the torn rotator cuff, he still has a cannon for an arm. With his team trailing in the top of the eighth, he throws a Hops runner out at the plate on a nearly perfect one hopper, keeping the Browns’ deficit at two. After the game, he’ll claim it wasn’t a great throw (it was a foot up the line at most). By the time he comes to bat in the bottom of the eighth, the bases are loaded and the Browns trail by just a run. He rips a single that gives his team the lead for good. Barker hitting the game-winning single. Ted ChalfenIt’s easy to look at Barker and wonder what might have been, but he insists that he wouldn’t change anything. “There’s a lot of negative things that happened but, really, I can’t change any of the past and it made me who I am now, and I’m a much better person than I was.” That’s not to say that major league stardom wouldn’t have made Barker’s current situation easier. “Looking back now…well, you know, I work at a cemetery. Money would be nice.” But playing baseball was never about the money anyway. “I would have played for nothing. I just wanted to break every record that I possibly could. Had I made it, I would have been able to help my sister out a little bit more when she was younger.” “I would have played for nothing. I just wanted to break every record that I possibly could.” But Barker says that if their lives had been different his sister might never have met her husband and he might not have his seven year-old nephew Mason. “I would never change that, ever.” Being unable to change the past doesn’t bother Matt Barker, but not being able to fix all the hatred he sees in the world eats at him. “I feel like we could do so much better than we’re currently doing as citizens of the world. It makes me feel helpless and I don’t like it. We’re not getting anywhere without each other.” While he can’t singlehandedly solve the world’s problems, he can share his story in the hopes that it helps others avoid the same mistakes he made, and that it just might give a young gay player somewhere the courage to keep going. “I would rather have gone through what I’ve gone through, and if it helps somebody else that’s great. I don’t want anybody to go through what I went through. When people tell their stories, if it helps somebody, it was worth it.” As I walked away from his sister’s house in the evening twilight after our interview was over, I knew that his story had already helped out one person, and I had the feeling that it would help out many more in the future. If you look at a man’s face you won’t be able to know who he is, what he’s thinking, or what he’s been through, but if you look at Matt Barker’s face you’ll be able to tell that finally, for the first time in his entire life, he’s at peace with himself. That’s more than enough for now.